Reprinted from the JF Ptak Science Books blog.

This interview of L.M. Cox was conducted by Elizabeth Doyle in San Angelo (Texas), in 1937 as part of the WPA (Worker’s Project Administration) effort to record American oral history. We know only this of Mr. Cox: “L.M. Cox of Brownwood, Texas was born in Benton County, Arkansas, in 1858 and came to Brownwood in 1880. He engaged in the ranching business for a number of years before retiring.” I’ve got a feeling that this last sentence would be something like “Joe Dimaggio played baseball for several years before retiring”, perhaps intentionally droll, perhaps not.

The interview, a paper copy of which is located in the Archives section of the Library of Congress, follows:

“The cowboy’s life as we know it was certainly lacking in the glamor which we see on our screens today,” says L. M. Cox of Brownwood, Texas.

“I have known cowboys to ride one hundred miles per day. I know this sounds unreasonable but they were off before daylight and rode hard until after dark. Their usual day’s work was to be off as soon as they could see how to catch their horses, throw the round-up together around 10 o’clock then work cattle or brand until dark and often times stand guard one-third of the night after that.

The usual ride was sixteen hours per day. No Union hours for them. It was from daylight until dark with work, and hard work as that. One cowboy complained of having to eat two suppers, so he quit, packed his bed and left. In about three months he returned, carrying only a bull’s-eye lantern, saying that where he had been working he needed only the lantern and had no use for the bed.

“Each cowboy had his mount, which usually consisted of ten or twelve horses and he rode four each day. Many of the horses were remarkably trained and like their owners, had their good and bad points. My own horse would tell his age by pawing on the ground and I have been criticized for saying that he could tell marks and brands but I know he could.

“There were few buffalo left, but there were antelopes in vast herds on both sides of the Pecos. I have seen hundreds of them on one drove, also black-tail deer. We could rope the deer but not the antelope. They were too swift on foot, faster than our fastest horses.

“In the late 80’s and early 90’s came the covered wagons and then the sheepman. We stood the covered wagons pretty well but it took a long time to get on friendly terms with the sheepman. They were sure enough trespassers in the cowman’s eye. One sheepman got his flock located on some good grass and the cowmen came along and ordered him off their premises. ‘I can’t go now,’ the sheepman complained, ‘I have lost my wagon wheel.’ Cowboys always had a heart and tried to be lenient but they also hated deception. One of the cowboys who had heard this gag before, looked around a bit and found the missing wheel hidden away in some mesquite bushes. The sheepman was hustled away in a hurry.

“In the late 80’s and early 90’s came the covered wagons and then the sheepman. We stood the covered wagons pretty well but it took a long time to get on friendly terms with the sheepman. They were sure enough trespassers in the cowman’s eye. One sheepman got his flock located on some good grass and the cowmen came along and ordered him off their premises. ‘I can’t go now,’ the sheepman complained, ‘I have lost my wagon wheel.’ Cowboys always had a heart and tried to be lenient but they also hated deception. One of the cowboys who had heard this gag before, looked around a bit and found the missing wheel hidden away in some mesquite bushes. The sheepman was hustled away in a hurry.

“Early days were hard on all stockman. With sheep selling at 75¢ per head, wool at .04¢ and cattle no better, a panic seemed evident.

“Neglect of herds caused lots of cattle rustling, stealing, burning of brands, etc. Many tales were told of mysterious increases in herds, one fellow had an old red cow that fruitfully produced twenty mavericks in one year. Another with a yoke of oxen reported an increase of twenty-six in a short time.

“We never heard much complaint about hard times. People thought about a lot of things more than they did money then, ’cause it didn’t take so much money to live

.

“No cowpuncher ever talked much. Ride further and talk less, few words and fast action, were rules which they followed pretty close

“The president of a big cattle company who resided in the North, came down to the camp once and was late getting there. When he arrived the boys had all either gone to sleep or out on night guard. He had one of those new-fangled talking machines with him and he turned it on out there under the midnight skies and all the punchers stampeded.

“No respectable cowman ever wore any other footwear but boots, and the spurs were never removed only when the boots were being cleaned.

“A stranger rode up to our camp one day and announced himself as a cow buyer. ‘He’s a damn liar,’ whispered one old puncher, ‘look at them there shoes he’s a-wearin’.’

“Cowboys lay awake nights trying to think of “good ones” to play on the tenderfoot. We tied an old cowboy to a tree once and told the tenderfoot that he was a madman, had spells and was very dangerous. At the appointed time the cowboy broke loose and the new comer made it to town, five miles on foot, in a very short time.

“Boiled beef and Arbuckle Coffee was our standby. The boys used to say if old man Arbuckle ever died they’d all be ruined and if it wasn’t for Pecos water gravy and Arbuckle Coffee we would starve to death.

“There were two things that the cowboys were deathly afraid of and that was the Pecos River and rattlesnakes. The river was narrow and deep, with no warning as to when you were approaching the bank and a man was liable to ride right over into the deep water at night before he knew he was near it. Time, and many cattle drives, have worn down the banks to some extent but in many places it still remains a strange phenomenon of nature, with its smooth straight banks and no warning of your approaching a stream.

“We don’t have ranches any more; just windmill and pasture projects. These dipping vats, bah! We used to have to dip some of the punchers but never the cattle. I tried for awhile to fall in with the their new-fangled ways but when they got to roundin’ up and herdin’ in Ford cars I thought it was about time for a first class cowman to take out, so I guess I’m what you’d call retired. Just the same, the cow business ain’t what it used to be to the old timers and I’m not the only one who says that, either. Everything else changes though, so guess we’ll just have to get used to that like we do other things and if we can’t get used to it, quit.”

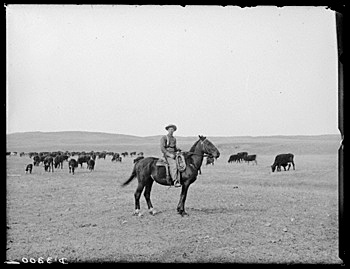

Photo credit 1: cowboy, high plains, Nebraska, 1886, courtesy the Library of Congress. Photo by the great Solomon D. Butcher, who made perhaps the greatest photographic record of western American life.

Photo credit 2: cowboy, high plains, Nebraska, 1886, courtesy the Library of Congress. Another in the Solomon Butcher series, 1886.